British Museum

|

British Museum The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects,[4] are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its beginnings to the present. The British Museum was established in 1753, largely based on the collections of the physician and scientist Sir Hans Sloane. The museum first opened to the public on 15 January 1759 in Montagu House in Bloomsbury, on the site of the current museum building. Its expansion over the following two and a half centuries was largely a result of an expanding British colonial footprint and has resulted in the creation of several branch institutions, the first being the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington in 1887. Some objects in the collection, most notably the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon, are the objects of intense controversy and of calls for restitution to their countries of origin. May 2011, Photo 492 |

|

|

British Museum The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects,[4] are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its beginnings to the present. The British Museum was established in 1753, largely based on the collections of the physician and scientist Sir Hans Sloane. The museum first opened to the public on 15 January 1759 in Montagu House in Bloomsbury, on the site of the current museum building. Its expansion over the following two and a half centuries was largely a result of an expanding British colonial footprint and has resulted in the creation of several branch institutions, the first being the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington in 1887. Some objects in the collection, most notably the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon, are the objects of intense controversy and of calls for restitution to their countries of origin. May 2011, Photo 41 |

|

|

British Museum Pediment May 2011, Photo 39 |

|

|

British Museum Pediment detail May 2011, Photo 39d |

|

|

British Museum Ramesses II, about 1270 BC. The upper part of a seated statue. The Younger Memnon statue is one of two colossal granite heads from the Ancient Egyptian mortuary temple called the Ramesseum at Thebes, depicting the pharaoh Ramesses II wearing the nemes head-dress with a cobra diadem on top. This incomplete statue has lost its body and lower legs; it is one of a pair which originally flanked the doorway of the Ramesseum. The head of its pair is still at the Ramesseum. It is 2.7 m high by 2m wide (across the shoulders), weighs 7.25 tons and was cut from a single block of two-coloured granite, with a slight variation of normal conventions in that the eyes look down slightly more than usual and to exploit the different colours (broadly speaking, the head is in one colour, and the body another). May 2011, Photo 47 |

|

|

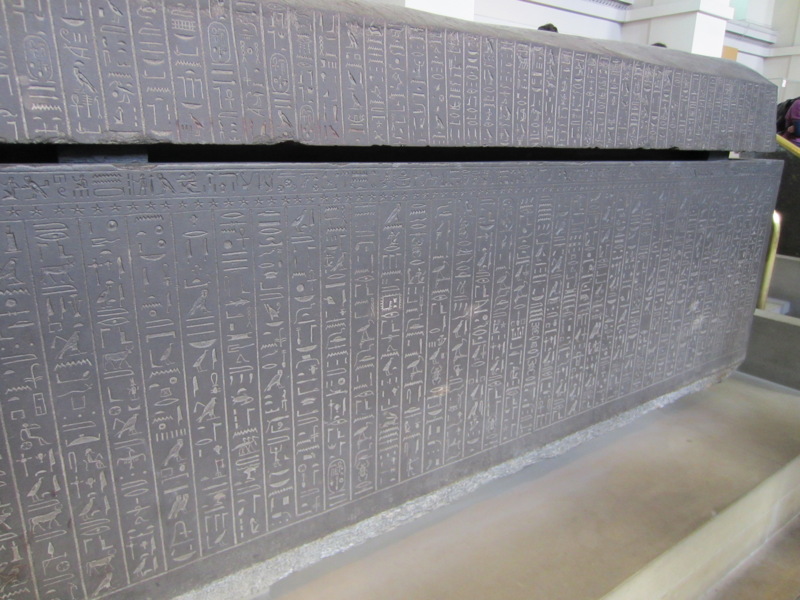

Sarcophagus of Merymose, about 1380 BC. British Museum Merymose was the viceroy of Kush in the reign of Amenhotep III (about 1390-1352 BC). Kush and Nubia were important sources of wealth for the ancient Egyptians, and during the New Kingdom (about 1550-1070 BC) produced much of the gold which the regime required. In the New Kingdom, the majority of anthropoid

containers for mummies were wooden coffins. However, there are a

number of sarcophagi made of hard stone. The sarcophagi of Merymose

are among the finest. Wooden coffins in the best burials tend to be

nested one inside the other, with a maximum of four coffins. Merymose

was able to afford three nested stone sarcophagi.

|

|

|

British Museum Limestone figure of a Horus-falcon, after 600 BC. The face and feet are particularly well executed. May 2011, Photo 51 |

|

|

British Museum Granite ram of Amum with King Taharqa, 690-664 BC The base of the statue is 1.63m long and 0.63m wide, and the statue is 1.06m high. The ram is lying on its stomach with its forelegs folded under it, and between them it protects a standing figure of King Taharqa. A hole in the top of the ram's head indicates where a gilded disk would originally have fitted. A hieroglyphic inscription runs round the sides of the plinth from front to back and proclaims Taharqa as the son of Amun and Mut, Lady of Heaven, 'who fully satisfies the heart of his father Amun'. May 2011, Photo 53 |

|

|

British Museum Black schist sarcophagus of Ankhnesneferibre, about 530 BC May 2011, Photo 56 |

|

|

British Museum The Gayer-Anderson Cat, bronze with silver plaque and gold jewellery, about 600 BC. The Gayer-Anderson Cat is an Ancient Egyptian statue of a cat made out of bronze, from the Late Period, about 664-332 BC. The sculpture is now known as the Gayer-Anderson cat after Major Robert Grenville Gayer-Anderson who donated it to the British Museum. The statue is a representation of the cat-goddess Bastet. The cat wears jewellery and a protective wedjat amulet. The earrings and nose ring on the statue may not have always belonged to the cat. While they certainly are ancient, an early photograph of the cat shows the statue wearing a different pair. A winged scarab appears on the chest and head, it is 42cm high and 13cm wide. A copy of the statue is kept in the Gayer-Anderson Museum, located in Cairo. The statue is not as well preserved as it appears. X-Rays taken of the sculptire reveal that there are cracks that extend almost completely around the centre of the cats body and only an internal system of strengthening prevent the cats head from falling off. The repairs to the cat are thought to have been carried out by Major Gayer-Anderson who was a keen restorer of antiquities in the 1930s. He is thought to have rediscovered the surface of the cat after the presumed corrosion had been removed. The cat was manufactured by the lost wax method where a wax model is covered with clay or clay and water until there is sufficient thickness. The clay can then be fired in a kiln and the wax flows out. The now hollow mould can be refilled with bronze. In this case the metal was 85% copper, 13% tin, 2% arsenic with a 0.2% trace of lead. The remains of the pins that held the wax core can still be seen using x-rays. The original metalworkers would have been able to create a range of colours on a bronze casting and the stripes on the tail are due to metal of a differeing composition. It is also considered likely that the eyes contained stone or glass decorations. May 2011, Photo 57 |

|

|

British Museum The Gayer-Anderson Cat, bronze with silver plaque and gold jewellery, about 600 BC. May 2011, Photo 58 |

|

|

Winged Human-headed bull/b>, Assyrian, about 862 BC, from Nimrud. This is one of a pair of guardian figures set up in the palace of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC) at the Assyrian capital Kalhu. Stone sculptures of mythological figures, sculpted in relief or in the round, were often placed as guardians at gateways to palaces and temples in ancient Mesopotamia. These figures were known to the Assyrians as lamassu. They were designed to protect the palace from demonic forces, and may even have guarded the entrance to the private apartments of the king. The figure has five legs, so that when viewed from the front it stands firm, while when viewed from the side it appears to be striding forward to combat evil. The 'Standard Inscription' of Ashurnasirpal, common to many of his reliefs, is inscribed between the figure's legs. It records the King's titles, ancestry and achievements. The figure was excavated by Austen Henry Layard, who worked in Assyria between 1845 and 1851. He suggested that these composite creatures combined the strength of the lion (or in this case, the bull), the swiftness of birds indicated by the wings, and the intelligence of the human head. The helmet with horns indicates the creature's divinity. May 2011, Photo 63 |

|

|

British Museum May 2011, Photo 67 |

|

|

British Museum Kate and the two Nimrud statues. May 2011, Photo 65 |

|

|

Lely's Venus, Aphrodite Statue of Nude Aphrodite known as "Lely's Venus" is Second Century AD. It originally belonged to the painter 'Sir Peter Lely then acquired by King Charles 1. It is clearly influenced by the four century BC Greek Sculptor Praxiteles. The nudity symbolizes a turning point in the culture, as previously only male statues were nude. This is a typical Hellenistic style sculpture shown by the elaborate hairstyle and the rendering of the body. May 2011, Photo 69 |

|

|

Venus, proconnesian marble, made in the 1st or 2nd century AC. May 2011, Photo 70 |

|

|

Nereid Monument, British Museum The Nereid Monument is a sculptured tomb from Xanthos in classical period Lycia, close to present-day Kinik in Antalya Province, Turkey. It took the form of a Greek temple on top of a base decorated with sculpted friezes, and is thought to have been built in the early fourth century BCE as a tomb for Arbinas (Lycian: Erbbina, or Erbinna), the Xanthian dynast who ruled western Lycia. The tomb is thought to have stood until the Byzantine era before falling into ruin. The ruins were rediscovered by British traveller Charles Fellows in the early 1840s. Fellows had them shipped to the British Museum: there some of them have been reconstructed to show what the East façade of the monument would have looked like. May 2011, Photo 75 |

|

|

Nereid Monument, detail May 2011, Photo 74 |

|

|

Nereid Monument The monument is now named after the life-size female figures in wind-blown drapery. Eleven survive, which would have been enough to fill the spaces between columns on the east and west sides, and the three on the north. Jenkins speculates that there might never have been figures on the south side. They are identified as sea-nymphs because various sculpted sea creatures were found under the feet of seven of them, including dolphins, a cuttlefish, and a bird that may be a sea-gull. They have generally been called Nereids, though Thurstan Robinson argues that this is imposing a Greek perspective on Lycian sculptures, and that they should rather be seen as eliyãna, Lycian water-nymphs associated with fresh-water sources and referenced on the Letoon trilingual inscription, which was discovered a few kilometres to the south of the site of the Monument. May 2011, Photo 642 |

|

|

Metopes of the Parthenon, British Museum The Metopes of the Parthenon are a series of marble panels, originally 92 in number, on the outside walls of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, forming part of the Doric frieze. The metopes of each side of the building had a different subject, and together with the pediments, Ionic frieze, and the statue of Athena Parthenos contained within the Parthenon, formed an elaborate program of sculptural decoration. Fifteen of the metopes from the south wall were removed and are now part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum, and others have been destroyed. They are famous examples of the Classical Greek high-relief. Although Arbinas ruled Lycia as part of the Persian Empire, the monument is built in a Greek style, influenced by the Ionic temples of the Athenian Acropolis. The rich narrative sculptures on the monument portray Arbinas in various ways, combining Greek and Persian aspects. The temple-like tomb had four columns on its east and west faces, and six on the north and south. It stood elevated on a substantial podium, decorated with two friezes: a shallower upper frieze above a deeper lower frieze. In the reconstruction in the British Museum, the podium consists simply of the two friezes above one layer of blocks, whereas Fellows's sketch of the monument showed a much taller structure with two substantial rows of blocks below the lower frieze, and a further two rows separating the lower from the upper frieze. There are also reliefs on the architrave, cella walls, and in the pediment. May 2011, Photo 643 |

|

|

Automation in the form of a ship, British Museum, about 1585 May 2011, Photo 648 |

|

|

Clock, British Museum May 2011, Photo 650 |

|

|

Sculpture, British Museum May 2011, Photo 651 |

|

|

Religion & Power in ancient Idalion 450-425 BC, The British Museum This man wears an elaborated wreath indicating he is a workshipper. The statue is typical from Cypriot art of this period, combining Greek and Persian dress and hair within the local tradition of carving limestone votive images. This statue was dedicated at an important sanctuary in the city of Idalian (modern Dali). May 2015, Photo 219 |

|

|

The Portland Vase British Museum, Perhaps from Rome, Italy, about AD 5-25 The most famous cameo-glass vessel from antiquity The scenes on the Portland Vase have been interpreted many times with a historical or a mythological slant. It is enough to say that the subject is clearly one of love and marriage with a mythological theme. The ketos (sea-snake) places it in a marine setting. It may have been made as a wedding gift. It is not known exactly where and when the vase was found. It is recorded as being seen in 1601 when it was in the collection of Cardinal del Monte in Italy. After the cardinal's death it was bought by the Barberini family where it remained for 150 years. Eventually, in 1778, it was purchased by Sir William Hamilton, British Ambassador at the Court of Naples. He brought it to England and sold it to Margaret, dowager Duchess of Portland, less than two years later, in 1784. In 1786 it came into the hands of her son, the third Duke of Portland, and it was he who lent it to Josiah Wedgwood, who made it famous through various copies. It was deposited in The British Museum by the fourth Duke of Portland in 1810 where it remained, apart from three years (1929-32) when it was put up for sale at Christie's, but failed to reach its reserve. It was purchased by the Museum from the seventh duke of Portland in 1945. May 2015, Photo 221 |

|

|

The Mechanical Galleon, about 1585 British Museum, Automation in the form of a ship There was a great fascination for automated machines at the end of the sixteenth century, particularly at the courts of Rudolf II in Prague and Süleyman 'the Magnificent' in Constantinople. Hans Schlottheim of Augsburg (1545-1625) was one of the most famous makers of these machines. This gilt-copper and steel automaton was designed to trundle along a grand table to announce a banquet. It takes the form of a nef, or medieval galleon, with sailors wielding hammers to strike the hours and quarters on bells in the crows nests. It also shows the time on a dial at the bottom of the main mast. Music is played on a small regal organ and a drum skin stretched over the base of the hull. The Electors of the Holy Roman Empire, led by heralds, process before their Emperor seated on a throne beneath the main mast. As a grand finale, it fires its cannons to produce a wonder of noise and smoke to entertain the guests. Although for many years, this clock was said to have belonged to Emperor Rudolf II himself, it is now thought that it might be the one described in an inventory of the Kunstkammer of the Elector of Saxony in Dresden in about 1585. Today, the clock is not quite in its original state. In the nineteenth century, missing main deck figures were replaced with copies made from existing original figures. May 2015, Photo 224 |

|

|

Pediment, British Museum

May 2015, Photo 227 |

|

|

Pediment, British Museum

May 2015, Photo 228 |

|